This is the fifth article in a series that aims to explore how subculture has changed in the last 30 years. Read part four here. New to the series? Click here to read part one.

The role of the media and the internet

Throughout the late 20th century, the flow of information came through mainstream portals (magazines, television, newspapers, radio) with underground media playing an important role for subcultures (magazines, newsletters, pirate radio).

This meant a small number of people controlled the news agenda and could filter information. They were gatekeepers.

London-based 1960s/70s underground newspaper Interntaional Times (IT), punk fanzine Sniffin’ Glue, 1990s rave culture magazine Eternity (I actually owned this issue), DJs from pirate radio station Radio Caroline, British counter-culture mag Oz, Kerrang!: the 1983 heavy metal supplement of Sounds magazine that soon become a magazine in its own right – outliving its parent title.

For subcultures and niche interest groups, the sources of information were few and often small, so the amount of information disseminated amongst groups often was relatively small.The small number of sources also meant there were a small number of opinions and niche taste-makers often had a monopoly – becoming king makers. If you liked hard rock and heavy metal in the late ’70s there was one radio show, no mainstream media or television. These influencers filtered and curated ‘good music’ for the subculture – they ‘set the news agenda’ for the scene. Characters like Alan Freeman and Tommy Vance became highly influential to that group. The NME was known as the ‘magazine that could make or break a band’.

The internet put the power to decide what was good, in the hands of consumers

In his 2016 mega-documentary Hypernormalisation, Adam Curtis describes the earliest stages of cyberspace and the internet. In the 1990s, former hippy John Barlow hoped that cyber space could offer the alternative way of being, communicating and relating to other humans that ’60s counter culture hoped to achieve. The Government and dominant culture had crushed the counter culture and absorbed its refugees in the real world, but cyber space offered a place that governments couldn’t control and Barlow wanted to get a flag in the ground first. In 1996, Barlow penned A Declaration Of Independence of Cyberspace with the aim of creating a place where nothing was policed and people were free to be who and how they wanted to be. While this is a utopia of the ’60s counter culture, it was clear that there was a ’90s desire for the same. Maybe it should come as no surprise that big business and individualism have always lived in uncomfortable symbiosis on the web.

Adam Curtis’ Hypernormalisation is 2 hours and 46 minutes of mind-blowing documentary – insight into Syria/US geo-politics, oil, Russian propaganda, the birth and morphing of suicide bombing.

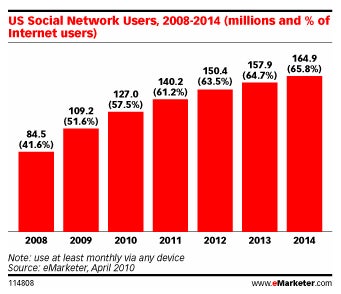

The internet put the power to decide what was good, in the hands of consumers through giving access to the finished product (music, video, books), and/or through giving people a platform from which to broadcast (social, YT, blogs). A fall in the cost of tech hardware was also a catalyst (everyone having a camera and video camera on their telephone and cheap/free editing software). This diminished the power of the few tastemakers and allowed a multitude of new – often amateur enthusiast – tastemakers to emerge. And so everyone became a critic: using social media and blogs to talk to audiences themselves.

Even the privileged ‘access’ of the mainstream media (celebrities, politicians etc.) could not be protected. The moment it was online it could be ‘stolen’ and proliferated. Even print-only titles were transcribed and posted online. (I remember working at a print title where PDFs were taken from the printing plant and pirated – and the same for our covermount CDs). The media no longer had anything of value – everything people wanted could now be accessed for free (apart from the paper it was printed on).

Marx would have loved it. So would Orwell. Not only had the means of production (of media) been delivered into the hands of ‘the people’, but access to information was now free and could not be controlled or manipulated.

There had long been a debate over who owned the airwaves. What gave the government the right to own and commercialise them? Surely the air belonged to everyone. Finally, the internet offered the chance to broadcast unregulated and for free.

Pirates: London’s Rinse FM (playing mainly UK garage), Eruption (’80s/90s rave station) and Kiss – only becoming legal in 1990. Despite recent ridicule, Tim Westwood was an immensely important part of the British hip hop scene breaking US artists and bringing new music to UK ears in a time when no legal stations were.

Importantly, because these guerilla outlets operated without commercial pressures, they often preferred their content for its honesty, authenticity, credibility and irreverence. Mainstream tastemakers not had competition, they were being superseded by ‘superior’ products. These media David’s could compete with mainstream Goliaths on an equal footing.

This allowed super-niches to emerge. Traditional media had had to be inclusive to be commercially viable (late-night ‘90s dance show BPM was the only show if its type on terrestrial TV and included a variety of subgenres), but now enthusiasts could create niche portals for fellow fanatics who only wanted very specific content.

Whereas traditional subculture titles brought a broad church together to form a in an inclusive world, the internet allowed everyone to belong to smaller niches online. For example: if you were the only metal head in your school in 1995, you may have had to make friends with goths, grungers or punks. Now you can befriend millions of people with your specific interests online – being part of a disparate community.

The 20th-century idea of a youth subculture is now just outmoded

In a 2014 article on ‘today’s youth culture’ for The Guardian, Alexis Petridis wrote:

“[What we] might call the 20th-century idea of a youth subculture is now just outmoded. The internet doesn’t spawn mass movements, bonded together by a shared taste in music, fashion and ownership of subcultural capital: it spawns brief, microcosmic ones.”

Add to the mix that brands were also taking advantage of the growing number of portals, platforms and channels – giving consumers more options.

With more and more successful super-niches, there was little room or use for a mainstream. The demise of the singular homogenising voice allowed further fragmentation of views and interests. Youth culture no longer had a centre of gravity and people drifted from each other to create a disparate miasma of an almost infinite number of slightly different individuals.

Heavy metal has birthed dozens of subgenres from death metal to black metal and thrash, to industrial metal and rap metal. All of these subgenres are often cross-pollinated for more other sub-sub-genres: blackened thrash, gore grind, post-black metal drone etc. etc.

Has the smartphone destroyed a generation?

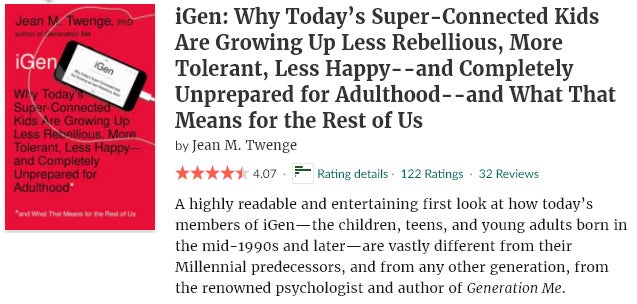

Jean M. Twenge wrote an article for The Atlantic that asked: ‘has the smartphone destroyed a generation?’

The quick answer is yes, but read the article anyway it’s fascinating and, if you have young children, a cautionary tale.

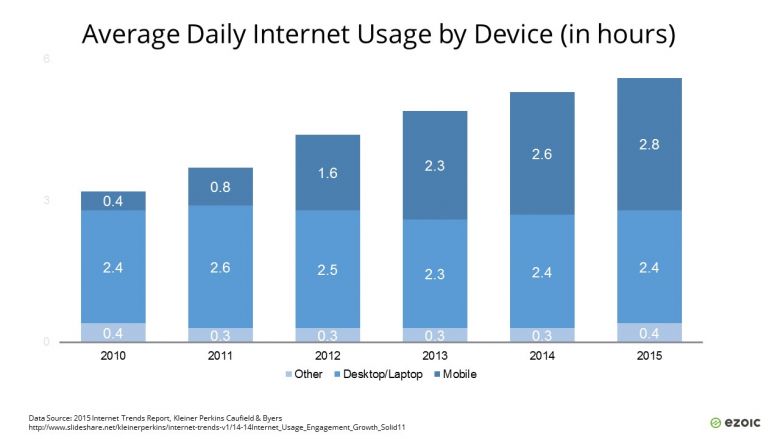

Mirroring my reflections in this series, Twenge states: “Millennials are a highly individualistic generation, but individualism had been increasing since the Baby Boomers turned on, tuned in, and dropped out… line graphs of trends looked like modest hills and valleys. Around 2012, I noticed abrupt shifts in teen behaviours and emotional states. The gentle slopes of the line graphs became steep mountains and sheer cliffs, and many of the distinctive characteristics of the Millennial generation began to disappear. I had never seen anything like it.

While I think traditional subcultures have been in decline for 20 years, Tweenge’s research cover the last five. Still, it corroborates and updates some of my findings.

Twenge’s book from which The Atlantic article draws much of its content

“The arrival of the smartphone has radically changed every aspect of teenagers’ lives, from the nature of their social interactions to their mental health. They are a generation shaped by the smartphone and by the concomitant rise of social media.”

While so much of subculture has about independence from mainstream institutions – family, parents, jobs, society – Twenge says: “the allure of independence, so powerful to previous generations, holds less sway over today’s teens, who are less likely to leave the house without their parents.” Adding that: “the number of teens who get together with their friends nearly every day dropped by more than 40 percent from 2000 to 2015.”

This doesn’t explain why subculture creation/emergence have declined, but it does give an interesting (if depressing) view into teenagers’ worlds; a world where addiction to something isolating and antisocial may have replaced something that people did to bring them together with like minds to give them value, meaning and purpose.

Collecting

The psychology of collecting examines why humans collect things. Archaeology shows that we have been hunting and gathering for more than 40,000 years – and even adorning our bodies with trinkets: beads, shells and feathers. We still don’t know why.

Maybe the need to gather berries, water (in egg shells), tubers and grubs to share has been woven into our evolution, just as squirrels bury nuts and magpies collect shiny things. The survival of this urge in all human societies and/or DNA suggests it has (or had) a use – a value.

Mesolithic skeletons with necklaces made from shells, bracelets and ankle rings.

But is collecting simply the result of acquisition? Is acquisition the urge? Reports on ideas of a disposable culture for the last 30 years suggests that acquisition is the urge, supported by shopaholics and the euphoria they describe in buying, not having. This would also support the Marxist idea that we are happiest when we create, not consume.

Few collectors complete a collection, they are always actively collecting, again suggesting that collection is more about acquisition, than it is having things. Collecting is only restricted by access (money, the existence of things, geography) and as those who have lots of access prove, they end up with monstrous collections of their particular penchant.The urge to acquire, and in this case eat, led certain Romans to gorge and make themselves sick, just so they could keep eating. Now we collect knowledge, we tick boxes on interests researched, videos watched, friends, updates, mini-wins of views, like or comments. And there is no limit. We are never full and we needn’t make ourselves sick to make room.

432 UK print magazines closed between August 2011 and July 2013

Addiction to social media is now well-documented as people no longer need to collect, simply drink straight from the faucet of interaction: another tweet, another like, another news story, another song.

Nothing is nurtured, nothing is cherished, nothing is valued and nothing is contextualised so nothing is meaningful, nothing is remembered and nothing coalesces into anything bigger than the isolated fragment consumed.

The internet: insider view

The internet is singularly responsible for all of it…

“The internet is singularly responsible for all of it – especially with regard to the homogenisation and blurring of the lines between specific subcultures.

“Instant access to subcultural style is also killing off certain aspects [of subculture]. If you wanted to dress exclusively in black back in the ‘80s, it was hard work. You had to dedicate a great deal of time to working on your outfits. There was only a handful of shops or market stalls that catered for a given look, so you often had to travel to London. There were literally clothes you couldn’t get in the right colour. Nowadays you can become an instant punk or goth simply by going online and buying it all at once without having to go outside.“Meanwhile social media keeps it alive and issues the fascistic decrees that engulf each subculture. Pop is literally eating itself.”

Alex Burrows

“The web has given subculture the perfect platform to thrive, but – by making it easy to find, consume and understand – the internet undermined the elitist, clique mentality that made it powerful in the first place. If everyone can do it, it’s not special.”

Scott Rowley

“It’s taken our attention away from commitment to a cause. We are so preoccupied with the latest stint or app or brand that we are always looking for what is next and not what is actually happening right now. Therefore not allowing a movement to grow.”

Jon Luis Jones

“Younger generations can express themselves in different ways now by using the internet as their soap box. Before social media existed the voice of a generation was heard and seen through music and fashion. It’s easier and faster to express oneself through carefully managed iPhone snaps on Instagram and Facebook.

“The internet allows a culture to develop without too much corporate influence. The internet is a shotgun of opinions, reviews and looks where it’s down to the individual to filter the content they take in. Before the output was controlled by magazines and editors.”

John McMurtrie

“The internet has given everyone a level playing field on which to get noticed. It’s made the notion of a true underground movement seem impossible, because, ultimately, everything and anything is available at the touch of a button. Although this in turn has made true crossover or mainstream success even more difficult.

“Ten years ago if you went to a student comedy night it would be packed, people just had a desire to see live comedy. Now it’s much harder to pull a crowd unless you have a TV comic topping the bill. With the amount of information and entertainment at their fingertips are people willing to take a punt on some unknown comedians? And is the mainstream willing to go and find exciting, cutting edge bands, comics and screenwriters? To take a risk? The margin for error can be disastrous for businesses trying to work a traditional model in this day and age. So why not play it safe?”

Stephen Hill

The internet killed subculture. I mean, it still exists, but only in people’s heads… Youth culture, subculture, any kind of culture is all about people coming together, physically, in a tribe. Sitting in front of a Mac w**king into infinity with a Guy Fawkes mask on is hardly Woodstock.

Ian Fortnam

“Social media has taken away from rather than added to the emergence of new subcultures. Digital technologies appear to aid established subcultures – the sharing and the validation that comes from being on the same page.”

Ali Divers

“It’s 100% made it easier to find new subcultures – to find the one you like the most. Without the internet you were only influenced by what you read in magazines or those around you, so to be able to look around, and try new things in a matter of hours is a great thing.”

Lewis Somerscales

“The internet has made gathering the information, music, images etc. easier, but it has probably watered down the intensity of the feeling that searching for it had ‘back in the day’. Easy access information must dilute any effect it has on them: if I can be influenced by 12 things in a week online, surely that doesn’t impact as intensely, so there isn’t going to be as much of a bond with others.

“I’m old [40s], so probably way out of touch with how these things affect people. Visiting the one rock shop in central London was a weekly/monthly event filled with excitement that logging on to Facebook can’t replicate.”

Scott Bartlett

Generations: from conflict to consensus to homogeny

Children dress more like than their parents than 80 years ago. Post-War subcultures set up a new uniform that hasn’t veered much from the James Dean – jeans and a t-shirt look. Casual clothes and (particularly in the last 30 years) sportswear have become accepted dress codes for all generations. Children have become happier and happier to dress more and more like their parents.

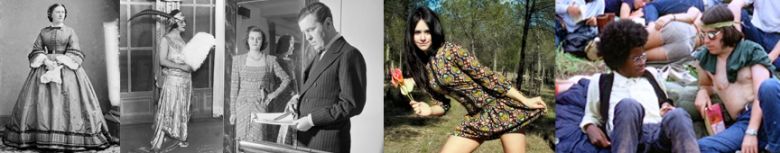

L to R: Victorians raised the young adults of the 1920 and 30s – many of those who could, distanced themselves from strict parents by their dress and activities. Post-war children (right) did the same, purposefully dressing differently from their parents (middle).

In 2011 The Independent reported that there had even been a reversal in this, with children influencing how their parents dress. In 1968, it would be unimaginable for a person born in the 1920s to dress like their hippie children. In 2017 Primark launched a mini-me line that allows parents to dress exactly the same as their children.

“Most heavy metal fans I knew were nice middle class kids who rebelled against their bourgeois parents by listening to noisy music and dressing like bikers.”

Jon Lilley

Kids are just ordinary, younger versions of their parents

Becoming your parents: subculture across generations, from the ’60s to the ’00s: The Rolling Stones, Status Quo, Van Halen and Metallica and Carl Barat of the Libertines.

Whether a cause or an effect, there seems to be less inter-generational conflict, the kind that played a role in teenage rebellion in the last half of the 20th century.

Do young people feel more affinity with their parents than in the 1960s?

Many who were teenagers in the 1960s agree, explaining that their parents just didn’t know how to relate to them: the long hair, the music, the sexuality, the drugs, the pop idols – and all of it so soon after a world war. The same was true of the youth of the late 1920s and 1930s.

Many children of the 60s and 70s who have raised millennials say that they understood things about their children that their parents just couldn’t. People who grew up with rock’n’roll, punk and rock may not have liked Marilyn Manson or The Prodigy, but they understood it: they understood the role of music, of uniform, of belonging.

Things that shocked a generation: Elvis’s hips, The Beatles rock’n’roll, The Sex Pistols swearing on TV, NWA’s violent lyrics, Marilyn Manson’s iconoclastic and blasphemous Antichrist Superstar album and live shows. What taboos are left to break?

“Youth could be a key factor in the decline or change of subculture. Young people don’t feel outside mainstream culture anymore. If this is the origin of subculture, then no wonder it is in decline.”

Ali Divers

“Most young people seem less inclined to rebel against their parents because their parents are much more easy going, and weren’t moulded by national service into staid conformity, consequently, there’s a lot less to rebel against. Between the generations at least.

“And so kids are just ordinary, younger versions of their parents who are simply older versions of them.”

Ian Fortnam

Society as a whole has changed. Children are no longer ‘to be seen and not heard’. They and their opinions are valid. Maybe having a voice means they no longer have to fight to be heard through music, clothes and slang.

Tattoos and body mod

Tattoos and body modification have long been used by individuals to identify themselves: broadly as outsiders and specifically – with certain styles and images denoting certain opinions and values.

In the early/mid-00s, the emo subculture rose from the hardcore punk, pop punk and heavy metal scenes (this is an over-simplification for brevity). The mainstream lapped up the music and fashion and soon emo fashions were available in Top Shop for anyone to buy – this was alongside a general rise of ‘rock’ fashion – from studded belts to Motorhead t-shirts. With fashion designers and high street buyers now versed in looking to the street not the catwalk for the season’s ‘look’, each new thing to come from the underground made it onto shelves within months.

Biker/Americana tattoos, gang tattoos, David Beckham.

With so many ‘tourists’, those who were (literally) hardcore fans needed new ways to show their genuine allegiance to this scene and its associated values. One way was tattoos.

Emos, goths and punks always saw themselves as outsiders and tattoos has often played a role in showing other-ship. So, in the mid-00s, it would play an important role for real ‘hardcore kids’ to show that they weren’t just ‘tourists’. Devildriver’s Dez Fafara once told me he had his lower lip and chin tattooed so that he could never get a proper job, it was a commitment to always being in a band.

Led by key figures in the scene (such as Bring Me The Horizon’s Oli Sykes and Gallows’ Frank Carter), young people started getting more and more tattoos, in more and more visible places.

Just as the fingerless gloves and skinny jeans had be co-opted by the high street, so too tattoos started to become mainstream. Celebrities such as David Beckham and Johnny Depp started to get more and more tattoos – as did fashion and perfume models from Jean Paul Gaultier to Diesel.

Just as a motorhead t-shirt, long hair or a beard had lost their specific semiotic meaning to a subculture, so too tattoos no longer meant, ‘I am really into hardcore’.

Alexisonfire/City & Colour frontman Dallas Green once told me that he regretted getting quite so many tattoos so quickly for this reason.

Oli Sykes, Dez Fafara, Dallas Green (by Thomas Hawk)

Brazilian Sepultura singer Max Cavalara got a tribal tattoo in the ‘80s because it represented an affinity and kinship for tribal people, indigenous people, underdogs. By the end of the ‘90s it had become fashionable and US steroid gym freaks were getting them, undermining their meaning. Though you might argue that Cavalara’s use was also a co-opting of someone else’s semiotic signal, changing its meaning from ‘I belong to a certain tribe’.

Click here to read the next installment of The Death Of Subculture. Part six: The Commoditisation of Subculture.

Share

Subscribe