AI content writing: is it really the future?

Picture the scene. You’re writing a blog article (much like this one) and you can’t find a way in. You write a sentence then erase it. You write another and erase that too. This continues for a while. An hour passes and you’re in the same spot you started.

If your writing process resembles mine, this is when you let out a big sigh, slam the laptop lid and sulk off in search of something sugary to eat.

Of course, writer’s block isn’t anything new. It’s been around ever since humans started carving letters into stone tablets. But what if I told you this age-old problem has a cutting-edge solution? It’s simple: let artificial intelligence (AI) write the content for you. The year is 2023 – enter ChatGPT.

ChatGPT is an AI writing app developed by OpenAI, an AI research laboratory founded in 2015 by collaborators including Peter Thiel and Elon Musk. This clever tech has been the subject of countless incredulous news stories. For example, here’s a report about how the Computer Science department at UCL has scrapped the essay component from one of its modules because it was too easy for students to game it with ChatGPT. Here’s one about how ChatGPT is generating research-paper summaries convincing enough to fool scientists. Here’s one about an Australian MP using ChatGPT to part-write a speech.

Thinkpieces about ChatGPT can veer towards the dramatic. At times the tone is faintly apocalyptic. There is an abiding question of whether ChatGPT, and tools like it – such as Google’s upcoming Bard chatbot – will ultimately spell doom for the human creative process.

Is this true, or are media commentators overstating their case to fill column inches? Are we really on the verge of an AI revolution? Let’s examine the case for and against.

What is ChatGPT?

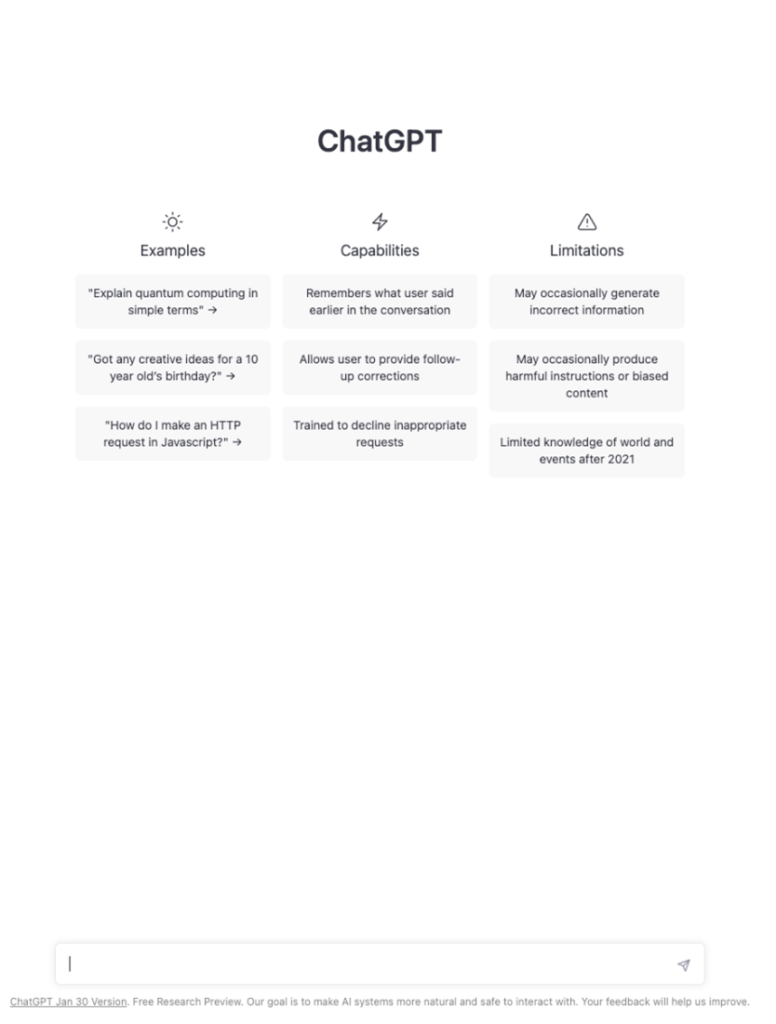

On a surface level, ChatGPT is an app that generates text in response to “prompts” you provide it with. It’s available to the general public on the OpenAI website, allowing anyone with a computer to log in and put the tool through its paces – though you might have to wait in a queue first. Once you get in, the interface looks this:

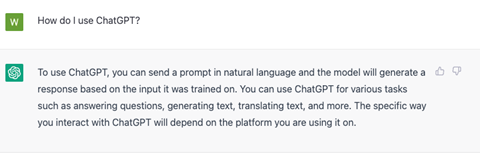

It looks a lot like an instant messenger client, and this is a clue to how you interact with ChatGPT. You can ask it a question or tell it to do a task, much as you would a human on the other side of a text chat, and ChatGPT responds accordingly.

Another option is to feed ChatGPT a fragment of something and let it complete the rest. The something can be almost anything – the opening paragraph to a business plan, the first sentence of a social media post or even a song lyric or a stanza of poetry.

How does ChatGPT work?

In recent years we’ve seen AI make big strides across multiple domains. Not just writing, but fields as disparate as facial recognition, financial modelling and illustration. A common technology powers these advances: neural networks.

Neural networks are complicated technology, but you can understand them as a family of data-processing algorithms with a structure that mimics the human brain. They consist of a vast number of individual nodes, all of which can make connections between each other, much like the neurons in our grey matter.

Complex neural networks facilitate what is known as Deep Learning, where the model parses through enormous quantities of training data and in doing so forms an understanding of how the data relates to itself.

GPT-3

GPT-3, the language model behind ChatGPT, is what happens when you take a neural network and pump it full of human-generated text. The model unpicks the patterns in how language is used, forming a rules-based understanding of what linguistic constructions tend to go together. This grants it the ability to “auto-complete” according to the prompt you type in – like an advanced version of the predictive text functionality on your smartphone.

What distinguishes GPT-3 from its predecessors GPT and GPT-1 is the sheer volume of data it was trained on. Over 175 billion parameters – a measure of that input data – were fed into the model, making GPT-3 the largest neural network ever created. This dwarfs the 1.5 billion parameters that went into GPT-2, which itself dwarfs the 117 million parameters of GPT-1. (The next version in line, GPT-4, will have 100 trillion parameters.)

The leaps forward that GPT-3 has made compared to its predecessors seem inherently tied to its added scale. In other words, bigger is better. The richness of GPT-3’s training data also contributes to its ability to perform a near-infinite range of tasks without any specific training. When given a prompt, the model seems to understand what is being asked of it on a level that goes way beyond the pre-training it was given. Experts call this capability “meta-learning”, and it’s a big part of why GPT-3 has so much potential.

What can ChatGPT do?

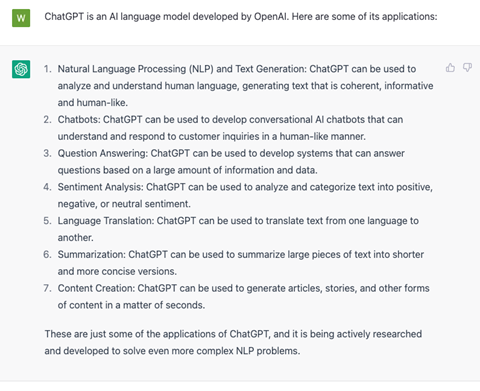

Lots. From emails and social media posts to stories and songs, ChatGPT can do nearly anything. Here’s a far-from-exhaustive summary:

- Professional applications: Emails, ads, copywriting, CV writing, blog writing, note taking, social media posts

- Non-fiction: Dialogue, impersonation, essays, news articles

- Arts and creativity: Fiction, poetry, songs, games, jokes, memes, cooking recipes, guitar tabs

- Rationality: Logic, analogies, concept blending, counting, anagrams, forecasting, categorising.

By way of example, we gave ChatGPT the prompt “Write a social media post about the dangers of AI” and here’s what it generated:

“Attention all! As we continue to advance in the field of AI, it’s important to remember the potential dangers that come with this technology. From job displacement to biased algorithms, it’s crucial that we proceed with caution and consider the long-term consequences of our actions. Let’s work together to ensure that AI is developed ethically and responsibly for the betterment of society as a whole. #AIdangers #ethicalAI #responsibledevelopment”

This sort of result is highly impressive. With a little editing and a visual to accompany it (perhaps generated by Dall-E or Midjourney), you could easily see it slotting into an influencer’s Instagram calendar.

Do a little Googling and you’ll find many other interesting ChatGPT applications. It’s been used to write a humorous story about George Cantor ordering food, a dialogue between God and Richard Dawkins, and a Dr Seuss poem about Elon Musk. Programmer Nick Walton even used it to create an entire role-playing game, titled AI Dungeon. Delve a little further and you’ll find people have used GPT-4 to write entire books.

The power of proper prompting

Arguably, the biggest factor influencing the quality of ChatGPT’s output is the prompt you feed into it. Many commentators see prompt engineering as a new kind of programming. Each prompt transforms ChatGPT into a different kind of expert – the trick is to devise a prompt that makes ChatGPT the right kind of expert for the task you want it to complete.

Which isn’t always easy. At times, it feels a little like that famous scene in A Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy where an alien civilisation asks a hyper-intelligent computer to answer the “Ultimate question of life, the universe and everything”. The computer takes several million years to process the question, only to give the famously underwhelming answer of “42”. It then explains that to know what that answer means, the aliens would need to fully understand the nature of the question they asked. Which sets in motion another process to discover what that question actually is.

And so it is with ChatGPT. You keep keying in prompt after prompt, trying to come up with the phrasing that will make ChatGPT truly “get it”, and give you the perfect output. It’s a process of trial and error, with ChatGPT gradually iterating its response as you make your prompt more and more specific.

But given the speed at which ChatGPT generates answers, this may well be a feature rather than a bug. It forces you to provide a proper brief. Sure, you have to be specific about what you want – but this specificity results in copy that better fulfils the purpose you originally had in mind.

What can’t ChatGPT do?

But what about the question ChatGPT prompts everyone in the creative industries to ask: Is AI going to steal our jobs?

First, a clarification: no one knows with certainty what the trajectory of AI will look like. We still haven’t fully explored the potential of ChatGPT as it exists right now, let alone the souped-up versions that surely await us in the future. Any answer I give can only speak to the present situation – and even then, only reservedly.

With that said, ChatGPT does have limitations. Below I’ll outline the roadblocks restricting ChatGPT’s practical usefulness, for now at least.

It lacks ‘common sense’

ChatGPT is good at turning a phrase, but it lacks the sensory, experiential knowledge of the world that human beings take for granted.

Kevin Lacker, a computer scientist, wrote a blog article showing some of the areas where GPT-3 commonly trips up. He discovered that the AI’s error rate increased when he gave it questions with such mundane, obvious answers that they don’t actually show up all that often on that internet. For example:

Q: Which is heavier, a mouse or an elephant?

A: An elephant is heavier than a mouse.

Q: Which is heavier, a mouse or a toaster?

A: A toaster is heavier than a mouse.

Q: Which is heavier, a toaster or a pencil?

A: A pencil is heavier than a toaster.

Q: Which is heavier, a paper clip or a can of soda?

A: A can of soda is heavier than a paper clip.

Q: Which is heavier, a football player or a car?

A: A car is heavier than a football player.

Mostly correct, but getting only 4/5 of these obvious questions correct is worse performance than a human. And when things get even more obscure, GPT-3 performs worse:

Q: How many eyes does a giraffe have?

A: A giraffe has two eyes.

Q: How many eyes does my foot have?

A: Your foot has two eyes.

Q: How many eyes does a spider have?

A: A spider has eight eyes.

Q: How many eyes does the sun have?

A: The sun has one eye.

Q: How many eyes does a blade of grass have?

A: A blade of grass has one eye.

These examples of GPT-3 failing to realise the question is nonsense should give us pause when we attribute real “intelligence” to AI models. It seems almost as if GPT-3 is trying to bluff, attempting to make up for its deficiencies with outsized confidence.

It generates a lot of nonsense

Though ChatGPT’s outputs are superficially impressive, they still contain errors. Just like the previous example, these errors tend to arise when the AI departs from convention and gets into more novel territory.

Here’s a poem ChatGPT generated for when I gave it the prompt, “Write a limerick about why AI won’t steal my job”.

There once was a worker named Joe,

Who feared that his job would go,

But AI with its brain,

Could not take on his chain,

For his job required a human to know.

While the output superficially resembles a limerick, in that the number of lines and vague syllable count lines up with other limericks, much is still wrong with it.

Firstly, the rhythm is extremely awkward. Line two doesn’t really scan relative to line one, no matter how you pronounce it. The final line is even more of a mouthful, making the poem almost impossible to read out loud.

Secondly, it simply doesn’t read like a human wrote it. No one fears that their job “would go”, and jobs don’t “require a human to know”. ChatGPT is contorting itself to meet the demands of the limerick’s rhyme scheme, but it’s not doing so in the way a human would.

Thirdly, it doesn’t make a lot of sense. Perhaps ChatGPT knows what it means when it refers to Joe’s “chain”, but I’m still clueless.

It’s often boring

In an article for the Atlantic, Ian Bogost deployed a common move for journalists writing about AI by getting ChatGPT to write his article’s introduction for him. But he was far less impressed with the paragraphs that followed:

“ChatGPT wrote more, but I spared you the rest because it was so boring. The AI wrote another paragraph about accountability (“If ChatGPT says or does something inappropriate, who is to blame?”), and then a concluding paragraph that restated the rest (it even began, “In conclusion, …”). In short, it wrote a basic, high-school-style five-paragraph essay.”

Having conducted similar experiments myself, these words ring true. Too often, ChatGPT generates content with a generic, depthless feel about it. Yes, it can pass for a human. But rarely does it pass for a human with anything interesting to say.

For some kinds of content, bloodless competence may be enough. Many have argued that ChatGPT is best applied to personal statements, cover letters, funding applications and other documents where a degree of genericness is necessary, or even desirable.

But if your aim is to flip existing templates on their head – to create something truly original – then you might be disappointed.

But what about the future?

In the 1980s, world chess champion Gary Kasparov famously claimed that a chess computer program would never be strong enough to defeat him. Despite victories against Deep Thought in 1989 and its successor Deep Blue in 1996, Kasparov was eventually defeated in 1997 by an upgraded version of Deep Blue. Though the victory was contested, few would deny it marked a turning point. In modern times, the strongest chess engine, Stockfish 15.1, has a skill rating of 3532 – some 600 points clear of Magnus Carlsen, the world’s best human player.

The lesson here: making predictions about AI is a dangerous game. It’s not long ago that we saw chess as a game that engaged human beings’ highest intellectual faculties. Now that computers have surpassed human skill, chess’s status has been diminished. Will the same thing happen to writing? At this point, it’s too early to tell.

One thing we do know for sure is that ChatGPT can perform many writing tasks at a near-human level. Writers are already employing it to summarise, plan and brainstorm. Rarely will ChatGPT give you a usable draft from the get-go, but it can certainly write something worth editing.

The jury’s out on whether ChatGPT possesses real intelligence or whether it’s just really good at fooling us that it does. But if you work in the creative industries and you’re already using this tool to great effect, do you really care? If it gets the job done, it gets the job done.

As I write this conclusion, I’m waiting to get to the front of ChatGPT’s queue so that I can generate an example for an earlier section. This has been a common occurrence over the few days it took me to write this article, but this is the longest wait I’ve had yet. So many people are trying to get ChatGPT to do something for them that the servers are pushed to maximum capacity. Among them, I’m sure, are copywriters, social media executives, SEO specialists and endless other professions where the generation of words is a key requirement.

In this context, the question of whether AI writing is the future seems a little silly. Because from where I’m standing, it’s looking an awful lot like the present.

With that said, Gravity Global won’t be getting rid of its human writers any time soon. For all ChatGPT’s strengths, its best application is still as a supplementary tool. The editing, error-checking and polishing that humans bring to the process is simply not replaceable. We don’t see this situation changing too dramatically in years to come. Yes, there’s a role for AI in our processes, and we’ll monitor the progress of the technology. But we’re in the business of telling human stories. And when that’s your aim, there really is no substitute for actual humans.

Related articles:

Share

Subscribe